PostActivation Potentiation Sample Workout

In a recently released book on power training for swimming, I spoke at length, and in fact dedicated an entire chapter to, a concept known in the strength & conditioning world as PostActivation Potentiation, or PAP for short. The section featured 26 pages, more than 20 sample sets, and an in-depth look at how we prescribe PAP at meets, and more specifically, how we use PAP in our everyday training here at Liberty to improve performance in the sprint events.

It is in the training where I will focus my thoughts today and will provide an example of a PAP focused power workout that our sprint group performed on Wednesday, October 19th, 2016. For those new to PostActivation Potentiation, or sometimes referred to simply as Potentiation, let me provide a somewhat brief overview. I say brief as the strength training literature regarding PAP can become quite muddled indeed, and for our purposes today, I believe it best to keep the science short and straightforward. If you prescribe speed assisted or resisted work with cords at meets or practice you are engaging in a form of PAP, and as it were, the swimming community has been the beneficiary of this phenomenon for quite some time. In short, PAP is a stimulus combined with a movement, intended to elicit a better (Citius, Altius, Fortius) effort poststimulus. Sport scientists differ in their beliefs as to why this works, but general "neural excitability" is often said to be a primary driver of the performance improvements, as from a primed neuromuscular system we see an increase in the recruitment of motor units and muscle fibers, combined with an increased rate of force development, among other factors.

In the book I share several examples, perhaps the most elementary being that of a weighted box jump with a vest into a box jump with no vest, or heavy squats followed by box jumps, etc.. While yes, the strength training gurus may find the squat example more similar to traditional complex training than pure PAP, I do believe we see a PAP effect from various forms of complex training; the two are certainly closely related. In swimming, we have the aforementioned cord work as part of a meet warmup, and other sports have their various methods of inducing PAP as well.

Cord assisted and resisted work in swimming is the tip of the iceberg, however, and there are myriad ways in which PAP can be prescribed to elicit faster performances at meets, workouts, and over the course of a career as well. I often find myself daydreaming of new and different PAP stimuli, and I write extensively about the possibilities in the book and in my training logs/journals as well. While I cannot prove the following, and I have not yet found a long-term study that corroborates, I believe instinctively that not only does PAP induce a short-term, single session improvement in performance (this much we know), there is a long-term adaptation that occurs in the CNS that improves performance over time as well. Thus we include PAP work in nearly all of our power sessions for our sprint group here at Liberty, and I believe wholeheartedly this type of work is a primary driver in their improvement in our program.

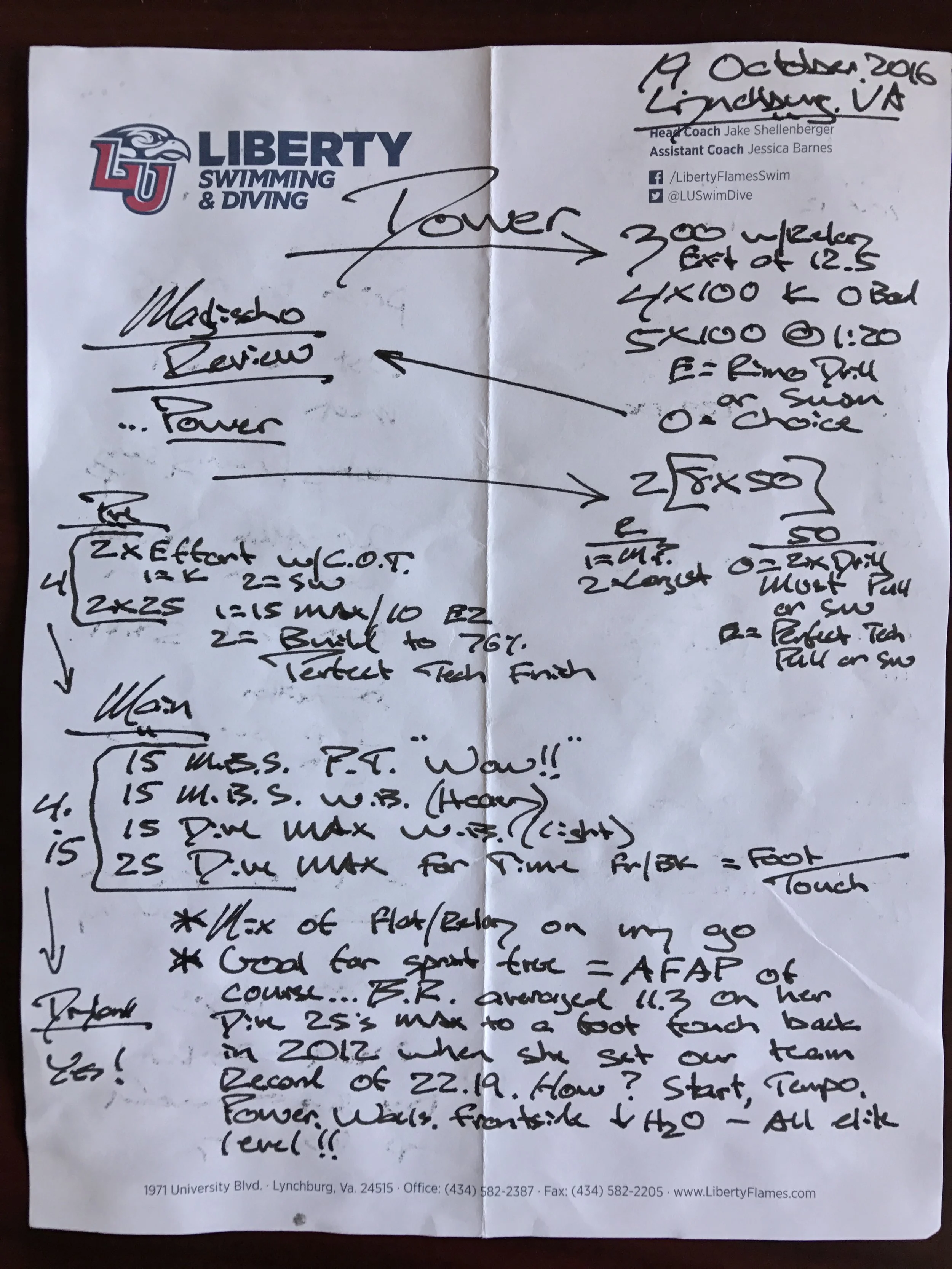

The workout:

I give every workout a title...This one I called "Dower"....Dive + Power

For the sake of brevity I will focus solely on the main set of this practice for the remainder of this article; know that everything prior was a warmup for body and mind in preparation for maximum effort swimming and maximum cognitive focus. One exception, of note, the "Maglischo Review." Please allow me a diversion. The Power of Belief in sport is strong indeed, and we must always be careful to consider the influence of said belief when planning training sessions. Always mysterious and somewhat mystical, it dabbles in the controversial as well. I use an example with recruits in regards to workout and overall program design as it relates to belief and performance improvement:

Situation 1:

Your dog writes your practices by randomly picking sets from a library of workouts each day. He has no knowledge of exercise physiology, no knowledge of program design, and no concept of sprint vs. distance and so forth. You might go the warmup for warmdown, the warmdown for the main set, or a power workouts day in and day out featuring Power Towers when your best event is the mile. But you love your dog, and your knowledge of exercise science is limited as well. You believe in his workouts wholeheartedly, knowing that of course they will help you improve. Perhaps best of all, your dog is on deck with you, and while he struggles to operate the stopwatch or call out the repeat times of your 50's, he's so darn cute that you smile and laugh your way through practice regardless.

Situation 2:

A computer designs your workouts. Loaded with the latest in sports science software, it uses your genetic code, the physiological demands of your best events, and your prior training history to regurgitate the world's best training program. Not only is the computer writing the best workouts, but it takes into consideration your diet, sleep habits, stress levels, and neuromuscular fatigue as well. But the practices are administered by robots in white lab coats, and you quickly tire of the constant poking, prodding, and the various wires running to and from your body. Do I need another lactate test you ask out of desperation, and you wonder why, with all of this fancy technology, they couldn't engineer the robot's voices to sound any better than Siri on a sick day? In the end, you have a hard time buying into this program, and you do not believe it will, in fact, make you faster. Surely there is a better way you determine, as you push off the force plate wall for yet another laser timed repeat.

I shorten this version for our recruits, but the point hits home just the same; more often than not they will swim faster in situation 1, thus we tell them to make sure they find a coach and training program they believe will make them faster. The goal with the "Maglischo Power Review" for our women is the marriage of the two, and this is the sweet spot where elite performance occurs. I use Ernie's Epic Swimming Fastest from 2003 as an expert witness testimonial if you will, as we know from basic human psychology that we are more willing to believe those who we perceive to be experts in the field. When you sit down to talk with a group of sprinters about the importance of power training for the 50, they listen. When you sit down to talk with a group of sprinters about the importance of power training for the 50, while holding 800 pages of big blue epic, and quote a Ph.D. with 13 National Championships, they listen harder.

And thus, the "Maglischo Power Review" summarized his thoughts on power training for the 50, found on pages 368-370 if you have the book and want to give it a look. My goal here was to reinforce and strengthen our belief in power training and PAP work, and specifically for the main set in this workout. While this might sound as though a futile attempt (what sprinter wouldn't believe in power training?), I do believe that priming the brain for a stronger belief, before the main set, while using an expert in the field, does indeed increase the power/level of the belief from the already high baseline. I have a theory I will share at the end of this article regarding this priming, one that we cannot prove, but one that I believe is evident in sport and life.

Main Set: We ended up having time for three rounds. In sets such as this one I hesitate to write a specific number of rounds, because frankly, the amount of work is secondary to the execution of each effort and the learning that occurs. This is race rehearsal, deep focus type of work, or deliberate practice as Anders Ericsson would say, and we take the time to do it as right. We also want maximum rest between rounds, as the goal is to prime the CNS, not fatigue it to the point of decreased performance. I used our school record holder in the 50, Brye Ravettine, as a goal for which to shoot; she averaged 11.3 or thereabouts for her dive effort work in 2012 when she set our school record of 22.19.

1 X 15 M.B.S. P.T. "Wow!!" From a Push, Choice of Gear

The first 15 Max Blast Swim effort featured the Power Tower and a heavy bucket. Heavy, of course, is relative to the individual student-athlete, their ability, experience level, etc.. There is not a one size fits all approach to going heavy on Power Towers, and certainly this is the case when there is a PAP focus as well. What elicits the desired neuromuscular response for a junior with plenty of experience in our program and three years of heavy buckets is, of course, different than what will produce a Potentiated state for a freshman. As for the specific PAP response, without having the ability to study it from a purely scientific standpoint, my guess is that we are recruiting more motor units and muscle fibers in the primary movers of the specific stroke, and we're also forcing the neuromuscular system to recruit said fibers at a faster rate. The wow is simply a fun way to say heavy, as in wow, did she just pull that much weight?

1 X 15 M.B.S. Heavy Weight Belt, From a Push, Choice of Gear

The second maximum effort swim featured a heavy weight belt. I speak at length in the book about weight belts, both as a general training aid and for producing a PAP response. "Weight belts work," to echo Sam Freas, and I believe wholeheartedly with coaches such as Freas and Cecil Colwin who advocate for the use of weight belts in training. You can add me to the list. I quote Colwin at length in the book, as he, more than any other coach I've read, articulates better the how and why of belt work, speaking to leverage and a bit of general physics in his analysis. His 2002 book entitled Breakthrough Swimming is a fantastic read for the cerebral minded coaches.

Heavy weight belts provide a total body, all around PAP effect, and admittedly, I struggle in my book to pinpoint exactly what is happening to the neuromuscular system during these maximum effort weight belt bouts, and how the effect of a weight belt differs from that of a Power Tower. Obviously, the resistance force vectors are different; slightly horizontal on the Tower vs. a more downward, vertical force from the weight belt, but what does that mean for the CNS? Is it possible to measure, and if so, how? I would love to see more research in this area - perhaps I will try to convince our Exercise Science folks here at LU to give it a look. We have a Human Performance Lab in our new Science Hall, and they might be interested in a swimming specific study featuring weight belts.

1 X 15 Dive MAX With a Light Weight Belt, No Gear

Starts can also benefit from PAP work similar to the weighted box jump example above, and it doesn't take much to elicit a PAP response off the blocks. The goal here was to produce a bit of neural stimulation for the start specifically, while not fatiguing the prime swimming movers and neural pathways in the process. This can be a tricky area to maneuver, as the PAP research points to a sweet spot of just enough stimulation for CNS priming, but not so much so that fatigue sets in and performance decreases. I have found over the years that 2-3 "heavy" efforts before the non-weighted effort are the perfect amount per round of work; any more and a bit of fatigue is present (and is visible) in the swim effort with no weight.

To give you an idea of heavy vs. light, our top sprinter went a 25-pound belt for the push effort and then a 12-pound belt for the dive. The push featured fins and paddles; the dive effort was again no gear.

1 X 25 Dive MAX For Time, Free/Back to a Foot Touch, Mix of Flat and Relay Starts

Yes. The results are spectacular, they are measurable, and even without a stopwatch, they are visible to the naked eye. You can see the effect of the Potentiation, with kick and stroke tempos increased, leg drive off the start increased, and some of the fastest frontside underwaters you will ever see from each student-athlete. Simply put, everything is faster after the PAP efforts.

For example, again using our top sprinter, without the PAP stimuli she routinely dives in the 11.3 - 11.5 range to the foot touch, and 10.9 - 11.0 from a relay start. In this workout she hit 11.1 from a flat start and 10.6 from a relay start, both lifetime best practice efforts and some of the fastest times in our program's short seven-year history (yes, I keep track of team records in dive 25's to a foot touch in practice and so forth).

The feedback from our women, speaking to the previously discussed belief and so forth, the feedback was all positive and exactly the result I wanted and expected when I wrote the set. The PAP effect in a workout such as this one is something our women can feel, and this feeling of new, raw speed gives them confidence that the training is working and improvements are occurring.

And finally, to my theory: Could the Power of Belief influence (positive or negative) the rate/success/efficiency of CNS/Neuromuscular response and adaptation? As per two examples:

- "I believe PAP works, I embrace it."

- "I do not believe PAP works, this is a waste of time."

The science will tell us that regardless of belief, changes to the neuromuscular system are occurring on the baseline, biological level, independent of whether one believes it is working or not...but does the belief for or against affect the responses in any way? Can it affect the adaptation? What is the result of such beliefs on the actual, measurable, scientific response of the CNS? Can we "think" or "believe" our way into faster and more efficient neural adaptation?

My goal with the "Maglischo Review" was to strengthen belief in this type of training and improve the effort and focus level of each repeat...could it be that the biological adaptation of the neuromuular system to this training is affected by the power of belief as well?